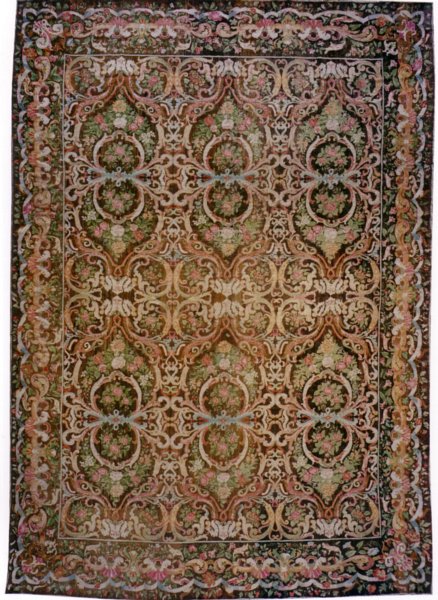

EXEMPLARY ANTIQUE AND CUSTOM CARPETS

UKRAINIAN, EARLY 19TH CENTURY OR EARLIER

Carpet nomenclature has customarily called all pile-knotted carpets from Eastern Europe ‘Ukrainian.’ While the Ukraine has a long tradition of weaving, this name ignores the rich tradition of weaving in neighboring Russia and Moldova where many of the carpets deemed Ukrainian are most likely to originate. Unfortunately, too little research has been done or published to enlighten our knowledge regarding the specific design and structural aspect of these carpets that would allow us to distinguish the regional attribution for each piece. We do know, however, that carpet weaving in Eastern Europe occurred under several different situations that are distinct from Western carpet production during the 18th and 19th centuries. In Russia, the Ukraine, and Moldova, large furnishing carpets were woven in workshops established on the estates of the aristocracy primarily for their own use and peasants wove small, more folk-like rugs at home. In 1716, Peter the Great established the Imperial Tapestry Factory near St. Petersburg to weave tapestries and carpets for the court, although the existing evidence suggests that the factory did not weave carpets until the late 18th or early 19th centuries. There is also documentation of commercial workshops organized by the nobility and merchants beginning in the early 19th century. In the few texts available, 18th century carpet production is discussed indicating active weaving on looms widespread across Russia and the Ukraine, but only trifling information is provided regarding the carpets themselves. Based on the limited source literature, we can presume that the most refined carpets in design and technique emanated from the sophisticated urbane societies of Russia and to a lesser extent the Ukraine and the more primitive, naively drawn pieces from the rural estates of the Ukraine and Moldova. Present day knowledge about these pieces is further hampered by rarity of the pieces themselves. As the majority of East European carpets were woven in non-commercial settings for an estates own use, pieces were not made in any great quantity. Most of the surviving examples also differ greatly from each other in technique and design due to the individual and localized nature of their production, making a direct comparison between extant carpets largely irrelevant in developing a stylistic classification for the group. The complex, superbly executed design of the carpet seen here indicates a Russian or Ukrainian origin from an estate workshop of the highest technical ability without concern for commercial viability in terms of cost. Interestingly, although this pattern manifests itself as a complete whole, it is actually composed of three separate vertical repeats of one design element, suggesting that the design is taken from narrow-loom brocades or other textiles. This design characteristic can be seen in a few other carpets and may suggest that these pieces are earlier in date than another known group of ‘Ukrainian’ carpets. The carpets of this latter group have more fully integrated designs indicating that they were woven from a professionally created cartoon in a more commercial, and perhaps later workshop. Traditionally, carpets of the type seen here have been dated to the 18th century, even though there is little documentary evidence of East European carpet production prior to the early 19th century. One recent publication has dated all of these carpets to the second half of the 19th century because their designs are reminiscent of the rococo-revival aesthetic prevalent in Western Europe during that period coupled with the scarcity of concrete evidence of Eastern European carpet weaving during the early to mid 18th century. An early date for the present piece seems plausible, however, as the carpet itself seems ancient in its weave, material handle and keen sense of design and drawing that lacks any inkling of the degeneration from the original usually associated with revival styles. Rather all aspects of this piece are pure and authentic to 18th century rococo ideals. In fact, the second-half 19th century French and English needlepoint carpets that reflect the taste seen here do not have a direct correlation in earlier carpets from their own countries; perhaps suggesting that these needlepoint pieces are reviving this earlier Russian design. When considering these intriguing Eastern European carpets, an obsession on their age is a mistake. In the end, it really doesn’t matter if this carpet was made in the18th century or 19th century, as it displays the technical and artistic dexterity and accomplishment expected in the best Western weaving and stands on its own as an incredible example of the carpet arts.Dimensions: 12' 10" x 18' 5"

Origin: Russia

Materials: wool pile, linen foundation

Predominant Color(s): brown

Stock Number: 2775